Overview

Queensland's public sector entities provide a range of services across Queensland, from healthcare and education to public transportation and emergency services. These entities include government departments, statutory bodies, government owned corporations, and controlled entities. Most public sector entities prepare financial statements and table these as part of their annual report in parliament each year.

Tabled 11 April 2025.

Report on a page

This report summarises the audit results of 236 Queensland state government entities, including the 21 core government departments.

The internal systems and processes (controls) entities have in place to support reliable financial reporting are generally effective. We audited more of the information systems this year and have found more control deficiencies that require attention.

Queensland Treasury is leading the whole-of-government approach to climate-related financial reporting. All Queensland Government entities need to understand the upcoming changes and consider the potential impacts on their financial reports and operations.

Financial statements are reliable

State entities’ 2023–24 financial statements are reliable and comply with relevant laws and standards. Ministers improved the timeliness – and therefore relevance for the public – of their annual reports (including financial information). They tabled them about 7 days earlier than last year.

The state’s expenditure grew this year

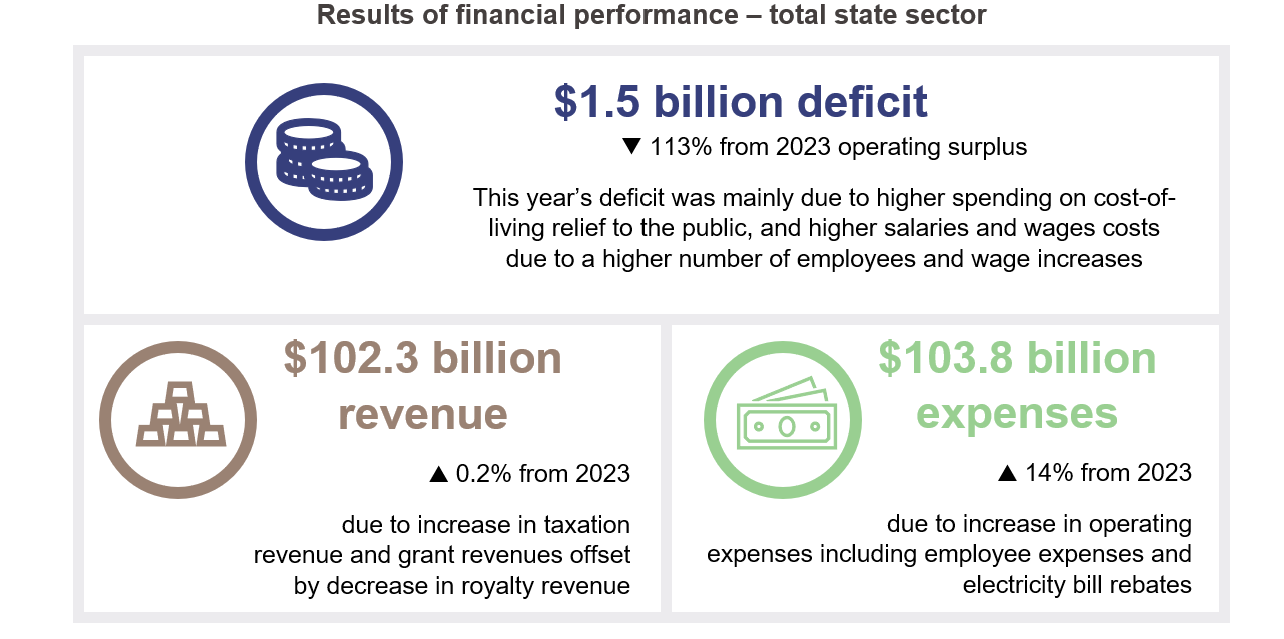

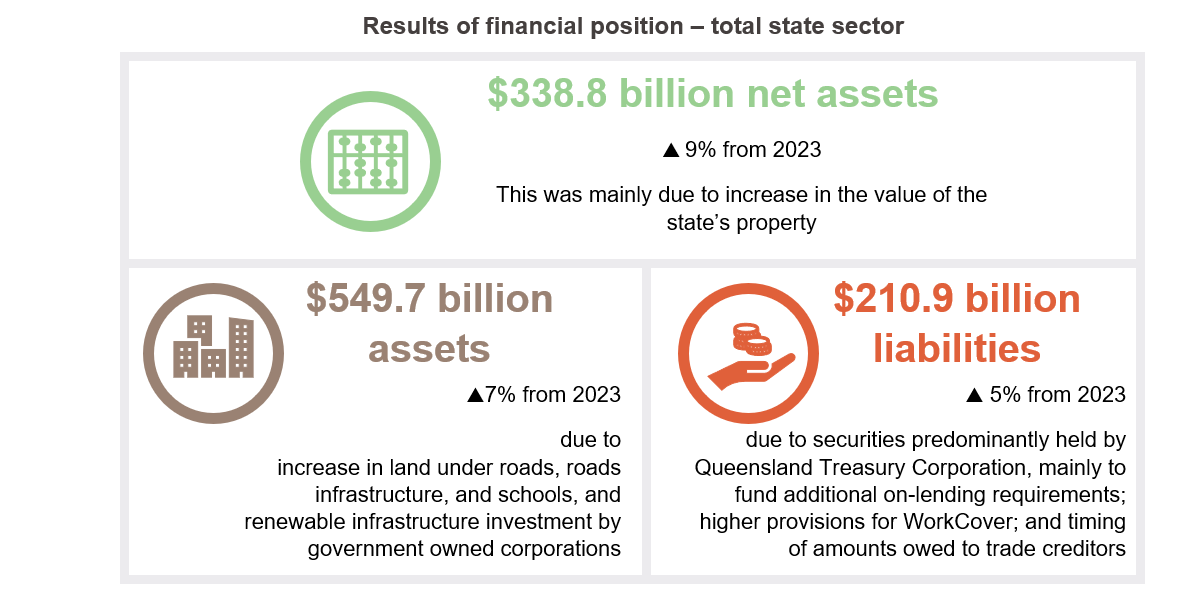

The total state sector moved from a net operating surplus of $11.1 billion in 2022–23 to a net operating deficit of $1.5 billion in 2023–24. This $12.6 billion decline was mostly due to higher levels of expenditure, including $8.5 billion for cost-of-living measures. Total revenue remained largely consistent with last year.

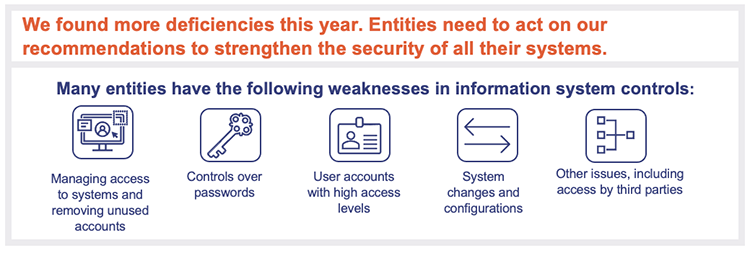

New information systems control deficiencies identified

We expanded the focus in our audits this year to better assess the controls entities have over access to their information systems and networks. Entities are increasingly relying on new technologies and facing heightened risks of cyber attacks. We found new control deficiencies in the systems across all state entities.

We continue to find recurring issues, not just in how access is controlled, but also in how risks are managed where information systems or data processing is managed by vendors external to government.

Because all entities need to strengthen these controls, we have created a new, dedicated chapter on information systems.

State entities have generally effective controls, but weaknesses are still present

While key controls at state entities are generally effective, entities do need to improve their controls over payroll, accounts payable and expenditure, and procurement and contract management. Entities must have strong robust controls to reduce their exposure to fraud, legal, and reputational risks. Effective controls also ensure accountability and reduce the risk of overspending.

Strong governance also plays an important part in good internal controls with significant deficiencies related to governance identified at Gladstone Ports Corporation Limited.

1. Recommendations for entities

Status of recommendations made in State entities 2023

This year, we are not making any new recommendations. Instead, we are drawing entities’ attention to the recommendations from last year that require further action.

We have reported in a new, separate chapter information systems' controls and the related areas for improvement to the relevant entities. We discuss this further in Chapter 4.

For a full list of the recommendations from previous years and their status see Appendix E.

Reference to comments

In accordance with s.64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

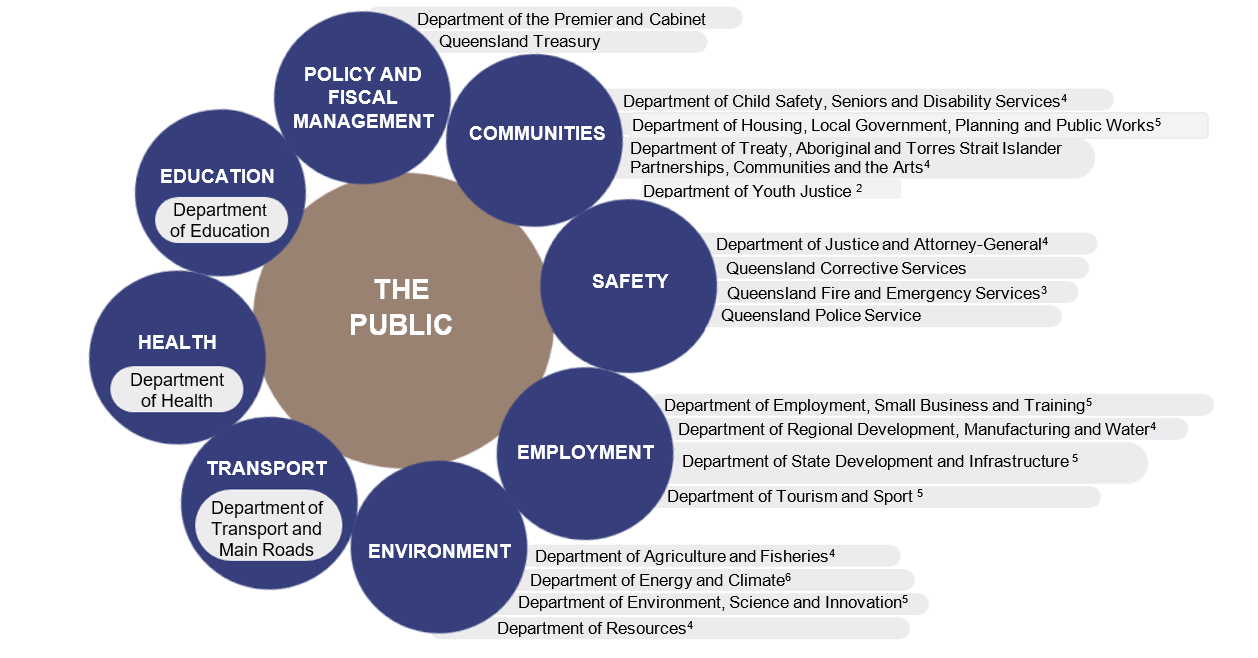

2. Entities in this report

This report analyses the results of financial audits for all Queensland state government entities, as summarised in Figure 2A.

Notes: *These do not include entities exempted from audit by the Auditor-General (see Appendix H), entities not preparing financial reports (see Appendix I), or entities audited by arrangement. **These are entities controlled by one or more public sector entity.

Queensland Audit Office.

Detailed listings of entities are shown in Appendix F and Appendix J, where we group them by the current ministerial portfolios following the November 2024 machinery of government changes. We use the names of the former departments throughout the report, as they were the entities we audited for 2023–24. Appendix D provides further information on the machinery of government changes.

We also prepare reports on certain sectors (such as energy and health) where we report our assessment of the financial reporting and internal controls of the sector. These reports can be found on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/reports-parliament.

This report covers all Queensland state government entities, including entities from those sectors, and it identifies learnings for all state government entities. ‘Core’ departments are those gazetted as departments under the Public Sector Act 2022, shown in Figure 2B. They are responsible for most public services provided by departments. As our report focuses on the audit results for 2023–24, we refer to the 21 core departments (referred to as departments in this report) that existed during that period.

The other 7 departments were established under the Financial Accountability Act 2009. Examples include the Electoral Commission of Queensland, Legislative Assembly of Queensland, Office of the Governor, and the Public Sector Commission.

Notes: 1 Renamed in December 2023. 2 New department in December 2023 and renamed in November 2024. 3 Renamed in July 2024. 4 Renamed in November 2024. 5 Renamed in December 2023 and then again in November 2024. 6 Renamed in December 2023 and abolished in November 2024.

Queensland Audit Office.

How we present this information

The Queensland Audit Office’s dashboard, QAO Queensland, brings together important information about the finances and services of Queensland state and local government entities. In doing so, it uses 3 common ways to divide the state into regions:

- local government areas

- statistical areas (used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and by state entities to collect and report on information, including the state budget)

- hospital and health service areas.

This allows users to search by an address and identify the services and the financial results for their local area, including for councils, education, health, water, and electricity. The dashboard is available on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/qao-queensland-dashboard.

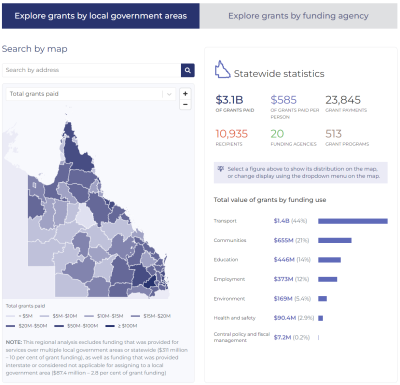

The following 2 data dashboards are also available on our website:

- Water data visualisation dashboard – this includes drought status, primary industries, and water storage facilities (total capacity and storage level as of 30 June 2024, where publicly available)

- Grants data visualisation dashboard – this explores grants paid by the Queensland Government, either by local government area or by funding agency. This interactive tool uses public information available on the Queensland Government Open Data Portal to summarise the number and value of grants paid. It also categorises grants into funding uses, recipient types, and funding agencies.

3. Results of our audits

This chapter provides an overview of our audit opinions for Queensland state government entities. It also provides an update on key transactions and balances.

Chapter snapshot

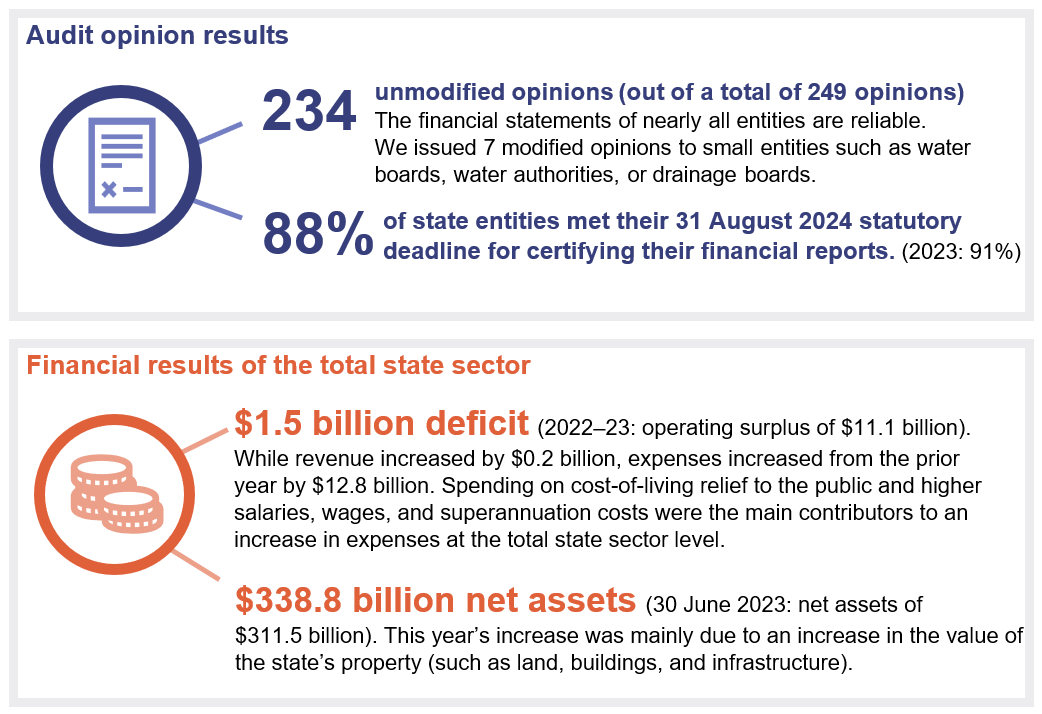

Audit opinion results

We issued unmodified opinions for 97.5 per cent of the 2023–24 financial statements we had audited (2022–23: 97.6 per cent) as at 14 March 2025. Most entities (88 per cent) had their audit opinions certified within their legislative deadlines (2022–23: 91 per cent).

All the departments, government owned corporations, and all but 7 statutory bodies (being 4 water authorities, 2 water boards, and one drainage board) received unmodified audit opinions.

We express an unmodified opinion when financial statements are prepared in accordance with the relevant legislative requirements and Australian accounting standards.

Figure 3A summarises the audit opinions we issued for 236 entities for their 2023–24 financial statements, and Appendix F provides the details. Appendix K provides a list of entities for whom audit opinions have not yet been issued.

| Entity type | Unmodified opinions | Modified opinions | Opinions not yet issued |

|---|---|---|---|

| Departments and entities they control (controlled entities) | 39 | – | 1 |

| Government owned corporations and controlled entities | 26 | – | – |

| Statutory bodies and controlled entities | 119 | 7 | 4 |

| Jointly controlled entities | 37 | – | 3 |

| Total | 221 | 7 | 8 |

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

We issued 13 unmodified opinions for entities audited by arrangement.

We included an emphasis of matter in our audit reports on 40 financial statements (2022–23: 43). We include an emphasis of matter to highlight an issue we believe the users of financial statements need to be aware of. The inclusion of an emphasis of matter paragraph does not change the audit opinion.

We did this to highlight:

- 33 entities for whom only certain accounting standards were used in the preparation of financial reports, and for whom the financial reports were only of interest to a small group of users

- 3 small entities that faced uncertainty regarding their ability to pay their debts as and when they fell due

- 4 entities that had either ceased operations or were likely to be dissolved in the coming year.

Modified audit opinions

We issued 7 modified opinions in 2023–24 (2022–23: 6).

We express a modified opinion when financial statements do not comply with the relevant legislative requirements and Australian accounting standards and as a result, are not accurate and reliable.

There are 3 types of modified opinions: qualified, adverse, and disclaimer (see Appendix F).

Appendix F lists the details of the entities that received modified opinions. All are small entities such as category 2 water boards, water authorities, or drainage boards. Of the 7 modified opinions we issued, we:

- qualified 5 opinions, which we do when the financial statements comply with relevant accounting standards and legislative requirements, except for a specified area. These qualifications related to

- entities’ valuation of property, plant and equipment, and intangible assets (for example, internally generated software)

- entities’ ability to prove the existence of property, plant and equipment, and intangible assets

- uncertainty as to whether debtors will pay all amounts that they owe, and as a result, whether the value of receivables in the financial statements are accurate

- disclaimed 2 opinions, which means we were unable to express an opinion as to whether the financial statements complied with the requirements of the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2019 or the minimum reporting requirements published by Queensland Treasury.

Opinions not yet issued

Appendix K lists those entities whose audits were not yet complete at the date of this report. These are small entities, and most are water boards, water authorities, or river improvement trusts that, as in previous years, did not meet the legislative deadline of 31 August.

Finalisation of overdue financial statements

When we tabled State entities 2023 (Report 11: 2023–24) in March 2024, 25 state entities had outstanding financial statements from prior years.

As at the date of this report, we have issued 10 audit opinions for these financial statements, including:

- 6 that were unmodified

- 4 that were qualified. These were for small water boards, and related to the completeness, existence, and valuation of their property, plant and equipment.

Appendix J provides details about these audit opinions.

In Appendix K, we list the 15 remaining financial statements that entities have still not completed for the 2022–23 financial year and earlier. Of these, the audit opinion for one water authority has been outstanding since 2015–16, and for a river improvement trust since 2017–18.

Other audit certifications

Appendix G lists the other audit and assurance opinions we issued, including:

- those requested by entities – to provide assurance over internal controls (systems and processes) at shared service providers (who deliver payroll, accounts payable, and information technology services to entities)

- to meet reporting requirements for grant agreements (funding from the state and federal governments) and regulatory information notices (which the Australian Energy Regulator uses to collect information from energy distribution entities to decide how much these entities can earn)

- to meet compliance requirements under legislation, including those for Australian financial services licences. (Certain entities must hold a financial services licence to issue or manage financial products or deal in certain investments.)

Entities exempted from audit by the Auditor-General

This year, 9 Queensland state government entities were exempt from an audit by the Auditor-General (2022–23: 6). Some are foreign-based controlled entities over whom the Auditor-General has no jurisdiction. For others, the Auditor-General assessed the entities as small and of low risk to the financial position of the Queensland Government as a whole.

These exempt entities are still required to engage an appropriately qualified person to audit their financial statements. Appendix H lists the reasons for their exemptions and the audit opinions they received.

Entities not preparing financial statements

Not all Queensland public sector entities prepare financial statements. This year, 146 entities were not required, either by legislation or the accounting standards, to prepare financial statements (2022–23: 116). We have identified them in Appendix I.

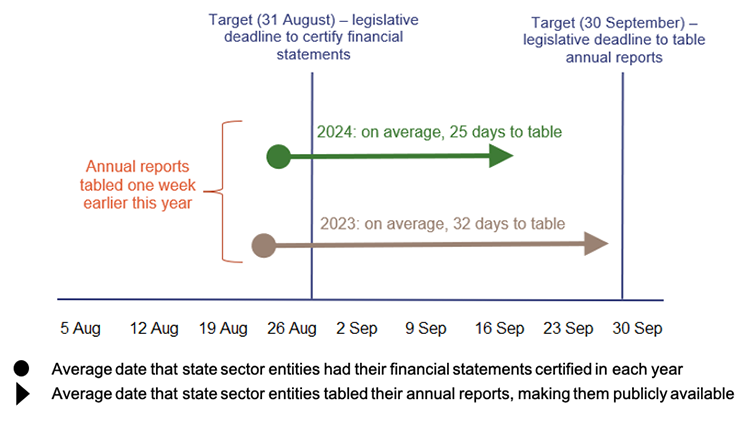

Earlier tabling of annual reports supports transparency

Because of the state government election in October 2024, tabling deadlines were brought forward to 13 September 2024 and as a result, the average time between certifying financial statements and tabling annual reports for state entities improved – reducing by a week, as shown in Figure 3B.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Timely tabling of annual reports improves transparency and stakeholders and the public benefit from having current, relevant information. We continue to encourage ministers to table annual reports in their portfolio in a timely way.

Preparing for upcoming financial reporting changes

Financial reporting standards evolve, and there are 2 new standards to be considered by reporting entities in future years. Climate-related financial reporting requirements will progressively affect some entities, with the largest government owned corporations reporting from 2025–26. There is also a new accounting standard for insurance applicable from 2026–27.

Climate-related financial reporting is changing from 2025–26 onwards

Climate-related financial reporting requirements are changing, with new sustainability reports including information on how entities govern and manage climate risks and opportunities as well as specific metrics and targets related to their greenhouse gas emissions. Queensland Treasury is currently finalising an overall approach for all state entities.

In September 2024, the Australian Government passed legislation requiring many entities reporting under the Corporations Act 2001 to make climate-related financial disclosures. The disclosures are outlined in a sustainability reporting standard issued by the Australian Accounting Standards Board.

Commencing in 2025–26, the first Queensland state entities to prepare climate-related financial reporting will include 9 entities, including the 8 largest government owned corporations. They will need to prepare a report on climate-related disclosures that are expected to cover governance practices, strategies for managing climate risks and opportunities, risk management, and relevant metrics and targets. Other large companies owned by government will apply this sustainability standard in 2026–27 and 2027–28 as required by the Corporations Act 2001.

The Queensland Audit Office will audit climate-related financial reporting disclosures in accordance with the auditing standards and Corporations Act 2001. Queensland Treasury is also considering how these sustainability standards might impact existing whole-of-government reports, including the Queensland Sustainability Report, in the future.

The state is preparing for climate reporting

Queensland’s departments and statutory bodies are not yet required by legislation to prepare climate-related financial disclosures. Queensland Treasury is leading the development of a climate-related financial reporting regime for state entities and is developing a framework, guidance, and tool for public sector entities to use in measuring greenhouse gas emissions.

Many government owned corporations already report on some of the required information through the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme.

Climate-related reporting: considerations for governance boards and audit committees Climate reporting is one part of the broader responsibilities for entities to manage climate risk. Queensland Treasury will be providing entities with more guidance and tools to facilitate reporting. In the meantime, governance boards should be considering the following:

All audit, risk, and governance committees should consider how their entities will report on and control their climate-related risks and opportunities. |

Some entities are also preparing for a new accounting standard on insurance

A new accounting standard, AASB 17 Insurance Contracts, will affect some Queensland state entities that provide insurance services such as WorkCover Queensland and Queensland Building and Construction Commission. The standard is intended to combine all existing insurance standards into one. It also introduces changes to how entities recognise and measure insurance contracts. This standard will apply to the public sector from 1 July 2026.

Entities are at different stages of assessing the impact, which goes beyond accounting adjustments. It will also affect how financial statements are presented, and it may require reviews of existing systems to ensure they are adequate. Preparation is crucial, as the standard requires comparative information to be presented in the 2026–27 financial statements.

Financial performance and position of the Queensland Government

The Financial Accountability Act 2009 requires the Treasurer to prepare annual consolidated financial statements for the Queensland Government. On 3 December 2024, the Auditor-General issued an unmodified audit opinion on the Queensland Government’s 2023–24 consolidated financial statements. This means the financial statements can be relied upon. These financial statements are included in the 2023–24 Report on State Finances.

This section highlights the results and financial position of the total state sector, which includes the General Government Sector, the Public Non-financial Corporations Sector, the Public Financial Corporations Sector, and their controlled entities.

The General Government Sector includes departments and agencies primarily funded by taxes and other government revenue. Their primary function is to provide public services that are non-trading in nature and that are for the collective benefit of the community.

The Public Non-financial Corporations Sector comprises government owned corporations that provide goods and services that are trading, non-regulatory, or non-financial in nature.

The Public Financial Corporations Sector comprises publicly owned institutions that provide financial services, usually on a commercial basis, and perform functions such as investment fund management and provision of loans to other government agencies.

Transactions and balances between entities within each sector are eliminated in the total state sector financial statements.

Financial results of the total state sector

The total state sector achieved a net operating deficit of $1.5 billion in 2023–24, representing a $12.6 billion decline from the prior year result. The state’s expenses increased by $12.8 billion to $103.8 billion in 2023–24.

Figure 3C shows overall revenue and expenses results for the year compared to the prior year as well as the movements of assets and liabilities in 2023–24.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the 2023–24 Queensland Treasury – Report on State Finances of the Queensland Government – 30 June 2024.

Major transactions and balances for the state

Understanding the financial performance of the state requires examination of key financial transactions and events. This section features an analysis of some of these transactions and events in 2023–24, focusing on changes in key revenue and expenditure sources.

We also provide a financial update on the Housing Investment Fund and the state’s interest in the Queen’s Wharf project.

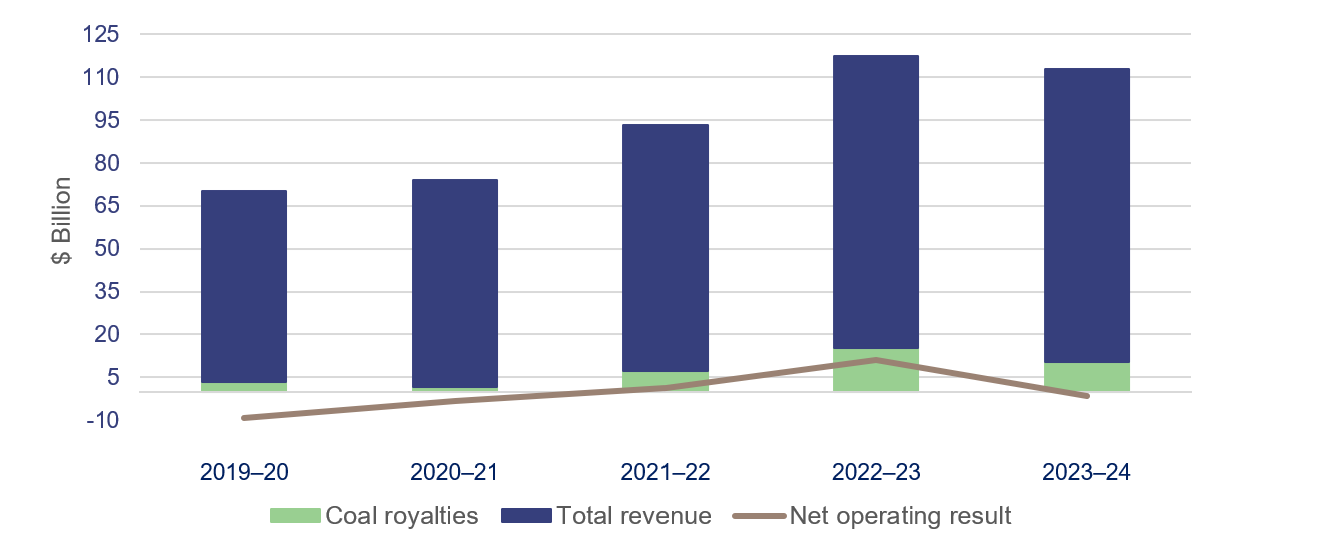

Coal royalties revenue is 10 per cent of Queensland’s total revenue

The Queensland Government’s total revenue and overall financial performance has historically been closely tied to the revenue it receives from royalties, including coal royalties, as shown in Figure 3D. This year, revenue from coal royalties made up 10 per cent of Queensland’s total revenue (2022–23: 15 per cent). The decrease this year was due to the fall in the global price of coal.

In July 2022, Queensland introduced a 3-tiered progressive royalty system that means coal producers pay higher royalties as the price they receive per tonne for coal increases.

The Queensland Government receives royalties revenue from mining companies who extract coal, metals, petroleum and gas, and other minerals.

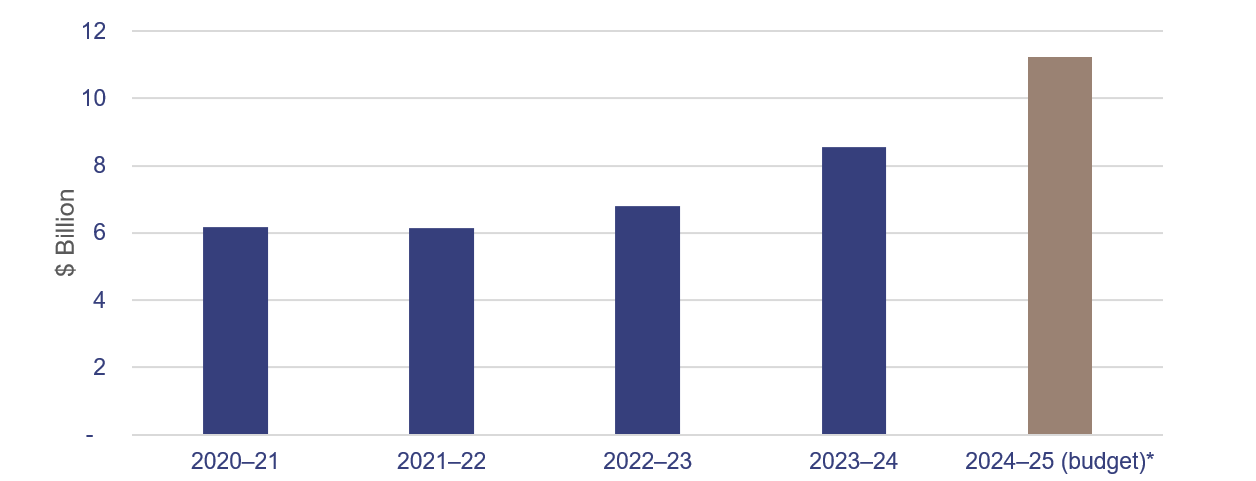

The state has spent more on concessions

The Queensland Government provides concessions (such as subsidies, rebates, and discounts) to reduce cost-of-living expenses for certain groups of Queenslanders. The value of the concessions budgeted to be paid by the total state sector has increased by 36 per cent over the past 2 financial years to $8.5 billion in 2023–24 (2022–23: $6.8 billion). It is expected to increase further in 2024–25, as shown in Figure 3E.

Note: *2024–25 (budget) represents the estimate the Queensland Government included in its Budget Strategy and Outlook 2024–25.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

The increase in 2023–24 is largely due to the Queensland Government’s response to higher cost-of-living pressures. In 2023–24, the state spent $8.5 billion on various initiatives including the additional electricity bill rebates. This represented most of the increase in concessions paid. Other initiatives include the free kindy for 4-year-olds, FairPlay vouchers, and school and community food relief programs. The state budget 2024–25 forecasts further concessions including further electricity bill rebates, a 20 per cent reduction in vehicle registration fees, and 50-cent public transport fares. The government estimated that the benefit of all concessions will be $11.2 billion in 2024–25.

Grants provided by the state

Government grants are payments or physical assets provided to recipients to support the delivery of government policy objectives. They can relate to services and initiatives to the public across a wide range of areas, including infrastructure and community programs.

In 2023–24, total state sector grants increased by $2 billion to $15.2 billion. Some of the main grant programs contributing to this increase are:

- grants paid by the Queensland Reconstruction Authority to councils for disaster recovery and resilience funding. These payments increased by $519 million to $1.4 billion. The Queensland Reconstruction Authority has programs underway with 76 councils (all but one), and it is still making payments for works for 46 natural disaster events that have occurred since 2019–20

- grants to non-state schools (Australian Government and Queensland Government funded). These payments increased by $367 million to $5.3 billion

- grants paid by the former Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works (DHLGPPW) including those paid for the Housing Investment Fund (explained below). These payments increased from $256 million to $504 million this year.

Each year, we publish our interactive Understanding grants dashboard: www.qao.qld.gov.au/understanding-grants. It can be used to explore and compare information on government grants in Queensland by local government area and funding agency. It also includes extra information relevant to understanding the local context for specific grants.

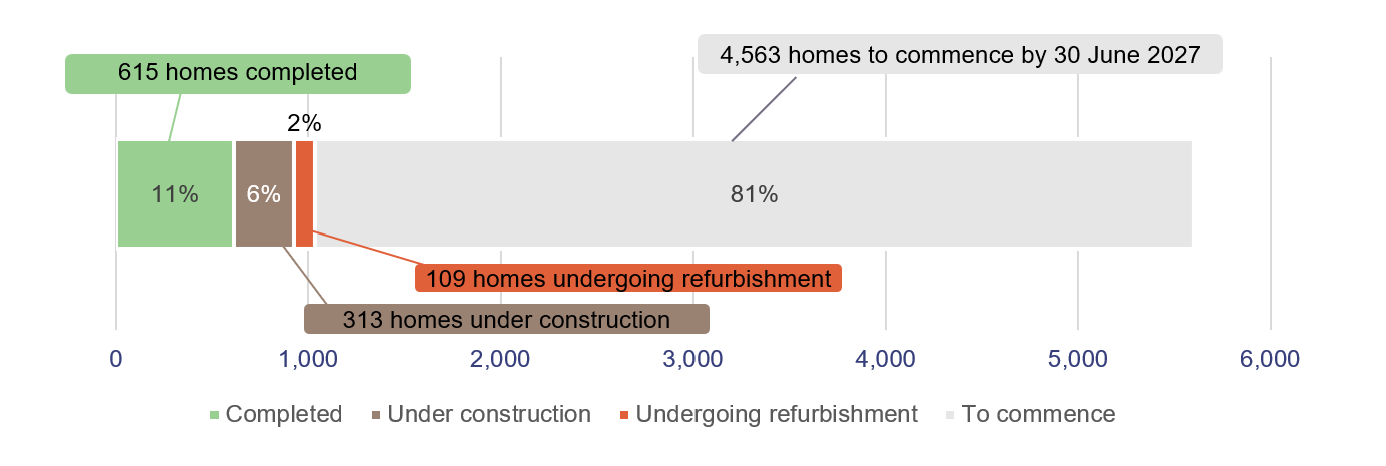

The Housing Investment Fund was established to support social and affordable housing

The state uses returns from the Housing Investment Fund to support programs aimed at increasing the availability of social and affordable housing for Queenslanders. In October 2022, the state doubled its investment in the Housing Investment Fund to $2 billion and committed to commence 5,600 social and affordable homes by 30 June 2027.

Key features of the Housing Investment Fund include the following:

- The $2 billion investment is held by the consolidated fund and managed by QIC Limited.

- The Housing Investment Fund provides $130 million in government funding per annum, supported by returns from the invested monies.

- To deliver planned targets, the former DHLGPPW provides subsidies and grants to developers, builders, community housing providers, and other institutions to deliver, finance, and operate social and affordable housing projects that meet housing needs.

As shown in Figure 3F, as of 30 June 2024, 1,037 homes had commenced; a further 4,563 more homes need to commence by 30 June 2027 for the state to meet its target. The state advised that as of 28 February 2025, 2,548 social and affordable homes have commenced.

Queen’s Wharf development has reached major milestones

Queen’s Wharf Brisbane is a $3.6 billion integrated resort development project. It includes a new casino, hotels, public spaces, and residential apartments. The state entered into a development agreement with Destination Brisbane Consortium (the consortium) for this project in November 2015. The developer of the Queen’s Wharf Project is providing the state with cash and non-cash consideration in return for the right to develop and operate the precinct.

This year the state continued to control several assets (including land and buildings) and liabilities. As at 30 June 2024, the state had received consideration related to the opening of the casino but because the casino had not opened at that point, it continued to be recorded as a liability. The liability, and land and buildings, will reduce as milestones are reached. Other transactions and assets will also be reported in future years.

The Department of Housing and Public Works (formerly DHLGPPW) is the owner of most of the land and buildings within the Queen’s Wharf Brisbane precinct. The state advises it is monitoring the precinct operations and the consortium’s delivery of contractual obligations, noting one of the consortium partners is experiencing deteriorating financial position. Figure 3G summarises the assets and liabilities recorded as of 30 June 2024.

Note: As a result of machinery of government changes that came into effect 1 November 2024, the Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works was renamed the Department of Housing and Public Works.

Compiled by Queensland Audit Office.

Deferred consideration is a liability an entity records when it has received payment but has not yet achieved the milestones required to recognise the amount.

The transfer duty provision is a liability to recognise the department’s obligation to pay transfer duty (a tax) to Queensland Treasury when it transfers the long-term lease on the integrated resort development to the consortium.

Completion and transfer of Rookwood Weir (Managibei Gamu)

The Rookwood Weir (Managibei Gamu) project was approved in February 2017. The aim was to provide Central Queensland with an additional source of water for the community and for agriculture and other businesses. The weir is a new 76,000 megalitre capacity weir on the Fitzroy River 66km south-west of Rockhampton.

The weir and supporting assets were completed in November 2023.

The project was jointly funded from $199 million from the Queensland Government and a $184 million contribution by the Australian Government. The project included construction of the weir and non-weir-related assets such as roads and bridges, with the non-weir-related assets expected to cost $113 million.

Sunwater Limited, a government owned corporation, constructed the asset on behalf of the former Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water, because of its expertise. It funded all costs beyond the $383 million contribution by the Queensland and Australian governments.

The department originally intended to own and operate the weir for up to 5 years post-completion to oversee its initial operations, ensure integration into the water supply, and manage the transition to Sunwater. However, in December 2023, the department advised Sunwater of its intention to transfer the ownership and control of the weir to Sunwater by 30 June 2024.

Financial reporting of asset transfers

On 21 June 2024, the department transferred weir assets valued in its accounts at $271 million to Sunwater. This transfer was reported in the department’s annual financial statements as a capital grant expense.

Because it uses a different methodology from the department to value assets, Sunwater recorded assets in its annual financial statements of $39 million for the weir and $86 million for related unsold water allocations. The unsold water allocations resulted from the construction of the weir and will be sold by Sunwater in the future. It received the assets and did not pay cash or other consideration to the department. Therefore, it was required by standards to record a liability called grant revenue received in advance, and this liability will be recognised as income over the weir’s useful life.

The recording of these transactions was in accordance with Australian accounting standards.

Valuation methodologies used

The department uses a different valuation methodology to Sunwater as they are classified to different sectors (refer to definitions on page 11). Both methodologies are allowable under Australian accounting standards, however, they result in materially different values.

This difference in asset value can be explained by the different valuation methods the entities used:

- The department used the cost approach, which reflects all costs relating to weir construction and includes works performed under external contracts using the invoice amount supplied by the vendor.

- Sunwater used the income approach, which values the asset based on the present value of future cash flows it is expected to generate from customers.

Both the department and Sunwater correctly disclosed the transfer of the Rookwood Weir assets in their 2023–24 annual financial statements. However, due to the differing valuation methodology, the overall financial impact to the state was unclear. We have made recommendations in Major projects 2024 (Report 9: 2024–25) about improving how asset transfers between agencies are undertaken and explained.

4. Focus on information systems controls

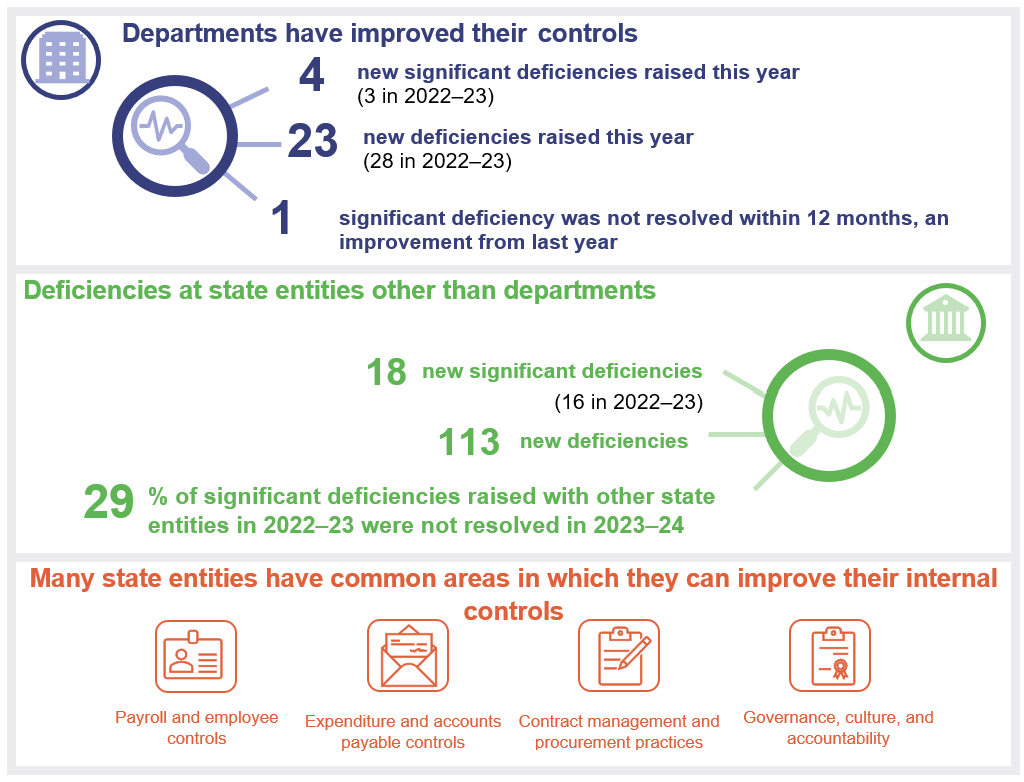

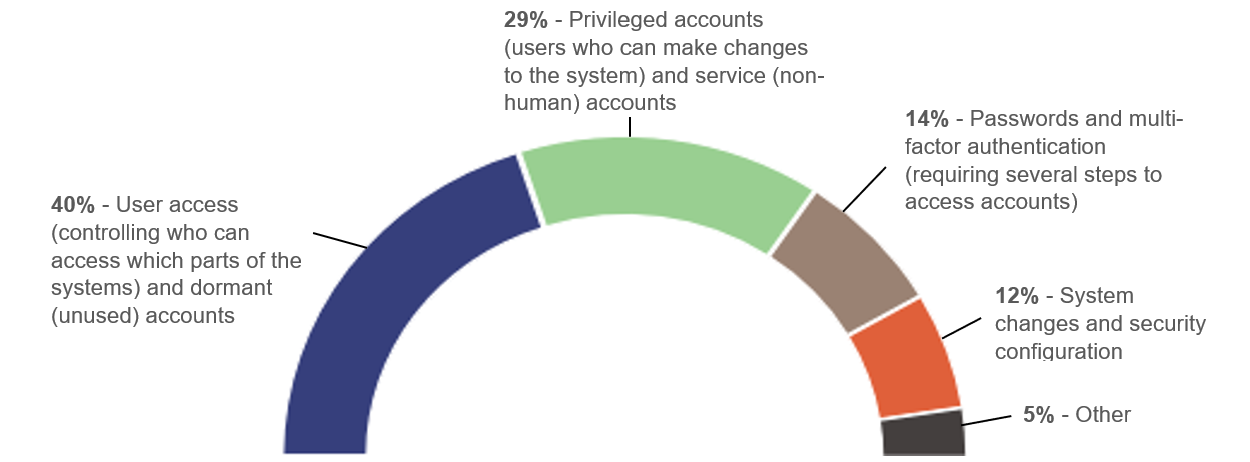

Recognising the collective need across government for more focus on the security of information systems, we have dedicated this new chapter to report on information systems controls. Sixty-five per cent of new deficiencies and significant deficiencies identified as part of our audits this year related to information systems controls. This year, we also included all deficiencies at state sector entities in our report, unlike past reports which only reported significant deficiencies for these entities.

Information systems are the hardware, software (applications), networks, and data that entities use to manage information. They include systems for finance, customer service, and asset management.

Systems are growing in complexity, and entities are increasingly using the cloud to access computing services through the internet. They are also more reliant on automated controls (which run without human involvement), and face increased cyber threats.

We expanded our audits to consider not just the applications state entities use, but also their underlying infrastructure – such as their databases, operating systems, and network access.

As a result of the expanding scope and complexity, we have raised a higher number of issues with management than we did last year.

Chapter snapshot

Weaknesses identified in information systems controls

In recent years, in various audits, we have made recommendations about the security of information systems to all state entities. If the entities act on these recommendations, they could better manage security vulnerabilities and the risk of inappropriate access to information.

Figure 4A shows the types of deficiencies in information systems controls we identified across the sector in our audits this year.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

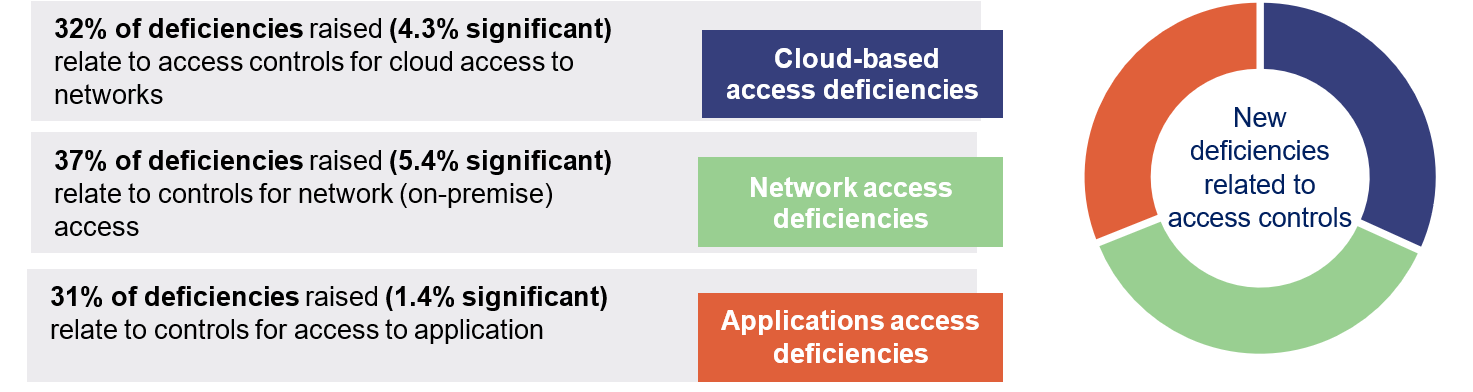

Access controls to applications, on-premise and cloud-based systems

Access controls ensure that only authorised individuals can access sensitive data and systems for applications, on-premise and cloud-based computing environments. They help maintain compliance with regulatory standards and protect the integrity and confidentiality of an entity’s information. We have identified deficiencies in each of these environments as outlined in Figure 4B.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Entities must effectively control their privileged accounts

Across Australia, over 87,400 cybercrime reports were made to the Australian Cyber Security Centre in 2023–24. Of those, 29 per cent were from Queensland. Public sector entities are considered particularly valuable targets for cyber criminals. Across Australia, 12 per cent of cybercrime reports were from state and local government entities.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre found that restricting accounts with privileged access is one of the mitigation strategies in ensuring the security of systems.

Privileged accounts have full system access or additional special access that is not usually given to standard accounts. The additional access includes the ability to, for example:

- change security configurations

- grant or change access for other users

- remove logging (recording) information

- access all data in the system (including sensitive data).

Not all privileged accounts are for humans. Some are system/service (non-human) accounts.

Malicious actors attempting to breach systems will often target accounts with these privileges because they can make significant changes to system configurations, bypass security settings and access sensitive data.

Entities are becoming more aware of the risks of not effectively managing privileged access within their information systems. There are tools available to help them manage these accounts. However, they still need to have adequate mitigating controls and robust processes to manage them.

Of the deficiencies we reported about information systems, 29 per cent related to how entities manage privileged access. All entities addressed or have an action plan to address the significant deficiencies we identified.

Administrative privileges for human accounts

We found that entities often do not:

- regularly assess and validate whether their assignment of privileged access to users is in line with the users’ roles and responsibilities; for example, they may have more access than they need

- implement stronger password controls for these accounts or have strong password controls in line with their own security policies.

Administrative privileges for non-human accounts

Entities create and maintain system accounts (known as service accounts) to perform system-related tasks that do not require human intervention. These accounts may need privileged access to perform the system tasks.

We found that some entities have:

- assigned service accounts with a level of privileged access they do not need

- enabled human users to access these accounts even though the accounts should be restricted for system use only

- not implemented strong password controls for these accounts in line with their own security policies.

Strong user access controls help reduce exposure to cyber threats

User access controls are security measures that regulate who can access specific resources in an information system, ensuring only authorised users can perform certain actions.

New, existing, and terminated users

We found many entities have robust processes in place to approve or modify the access of new and existing users, but further improvements can be made, including:

- removing system access for terminated users in a timely manner

- completely removing all system access or devices that enable access for terminated users

- performing regular reviews of user access to confirm that users are still working for the entity and that their access is in line with their roles and responsibilities.

Disabling dormant accounts and accounts used by guest users

Entities are not always performing regular reviews to disable dormant accounts and temporary access that is no longer needed. Malicious actors may attempt to use these accounts and go unnoticed as they could appear to have been performed by a valid and authorised user.

The Australian Cyber Security Centre released a joint alert with its equivalent partner agencies in the United States, Canadian, and New Zealand governments in February 2024. The alert detailed cyber espionage activity that successfully used an unsecured dormant account to breach a global supply chain.

Strong passwords and multiple layers of security help prevent unauthorised access

Good password practices can include enforcing strong, complex passwords that are regularly updated. Entities should also use multi-factor authentication to add an extra layer of security to their systems. This means users must complete a second layer of verification (such as a code from their phone) to gain access to a system. Even if their password is stolen, there is an extra step to prevent unauthorised access.

This year, 19 state entities needed to update their password configuration in line with their updated password policies to ensure their controls reduce the risk of breaches, unauthorised access, and compromised systems.

Managing third-party risks is essential for strong cyber security

Many public sector entities rely on other organisations, called third parties, for information system services and technologies to deliver their services to the public. These organisations are often also a part of entities’ frameworks for protecting, responding to, and recovering from external attacks.

Any system vulnerabilities in the third parties’ information systems could have significant flow-on impacts on the security of systems for public sector entities.

In State entities 2023 (Report 11: 2023–24), we recommended that all entities manage the cyber security risks associated with services provided by third parties by implementing the processes outlined in Figure 4C.

Queensland Audit Office.

Entities need to have robust processes to assess how well their third-party service providers are managing the security of their systems, and to determine if they can effectively respond to security incidents.

This year, we found that entities need to assess:

- their agreements with external providers of specific information technology services

- the level of access they provide to their service providers for information systems.

Entities often give these providers full access to their systems without checking if they actually need it to perform their tasks.

We have planned a performance audit in 2025–26 to assess in more detail how effectively public sector entities manage third-party cyber security risks.

Some Queensland Government entities provide information systems services to other government entities

There is a range of Queensland Government entities (for example, Centre for Information Technology and Communication and Queensland Health) that provide information technology (IT) services to other government agencies, so it is important that any security vulnerabilities or breaches in one Queensland public sector entity are sufficiently mitigated as they could also affect others.

Entities providing information systems services must make sure they can demonstrate to their clients that their systems (and the data they contain) are secure and meet industry standards. This can be done through independent reviews, certifications, or internal and external audits.

Implementing information security management systems

The Queensland Government Customer and Digital Group requires government departments to implement an information security management system (ISMS) and report each September on their progress on the implementation. Agencies must include all services, information, application, and technology assets within the scope of their ISMS.

Over the past 5 years, the Queensland Government Cyber Security Unit has noted an increase in the number of departments reporting that they now have an operating level of ISMS, meaning they are identifying and managing their risks, and continuously improving these processes.

The target set by the Queensland Government Chief Digital Officer for all departments is to achieve a 100 per cent operating level for their ISMS. As of 2022–23, departments reported an 86 per cent operating level of ISMS (results for 2023–24 were not available at the time of this report).

The Cyber Security Unit also collects and disseminates relevant security data through its cyber dashboard.

Entities need ongoing effort to effectively manage cyber risks It is essential that entities continuously manage cyber risks. We encourage them to regularly self-assess the strengths of their information systems against the recommendations we made to all entities in:

In Appendix L, we have also included a list of questions audit and risk committees can consider in assessing the effectiveness of their entities’ controls in relation to the security of information systems. |

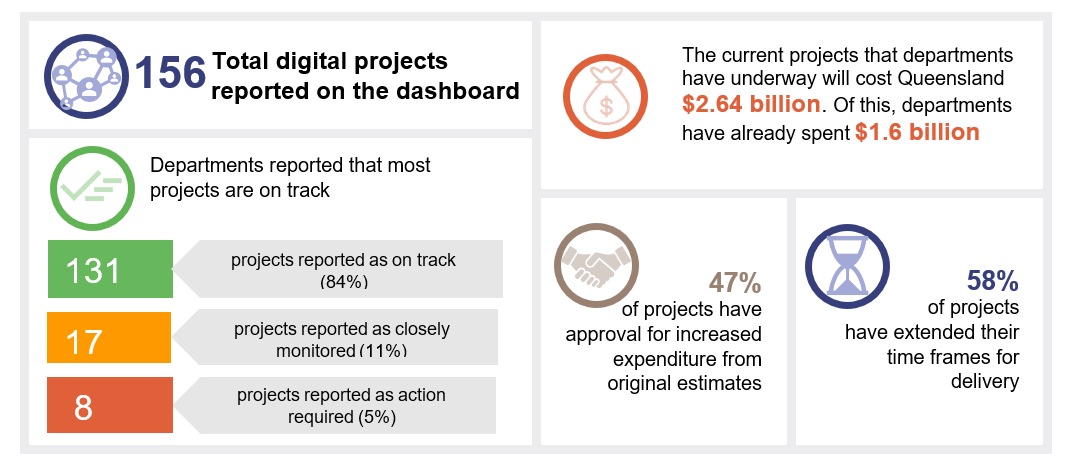

Planning for digital projects may need greater focus

As the environment we operate in rapidly evolves, successful system implementations shift from an operational need to a strategic priority. Being able to deliver digital projects effectively is critical for all entities.

While departments are assessing and reporting that most projects are on track, around half have had approval for increased expenditure from original estimates or have extended their time frames for delivery. For example, a project could cost more and take longer to deliver than initially expected due to changes in scope. Greater focus may be required during the project planning phases.

In Figure 4D, we have summarised the projects on the dashboard as of February 2025.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office, from the Queensland Digital Projects Dashboard.

Better practice guides for technology projects

On our website, we have published 2 better practice guides to help entities successfully deliver their projects. These are based on insights we have gained across various audits we have performed in relation to technology projects.

Queensland Audit Office better practice guides for technology projects Delivering successful technology projects This better practice guide summarises 5 factors that, managed and modified to suit, need to be present if entities are to protect and improve the success of their technology projects:

This guide will also help entities obtain the strongest benefits (such as efficiencies or improved security) from their digital investments. Learnings for ICT projects In this guide, we share some lessons learnt to guide all entities involved in information and communication technology (ICT) projects. |

5. Internal controls at state entities

Each year, we assess whether the people, systems, and processes (internal controls) used by entities to prepare financial statements are reliable. In this chapter, we report on the effectiveness of these controls at Queensland’s 21 departments and other state entities, and we also identify areas of focus in which they need to improve.

This financial year was also a period of change across departments and other state entities, with machinery of government changes leading to transfer of government functions between departments.

In this chapter, we focus on the main internal control-related themes and insights from our audits, excluding issues relating to information systems which we cover in Chapter 4. We also provide insights on emerging issues affecting governance and accountability.

Chapter snapshot

Note: This chapter snapshot does not include information systems deficiencies reported in Chapter 4. Appendix E provides a full list of recommendations from previous years and their status as of 30 June 2024.

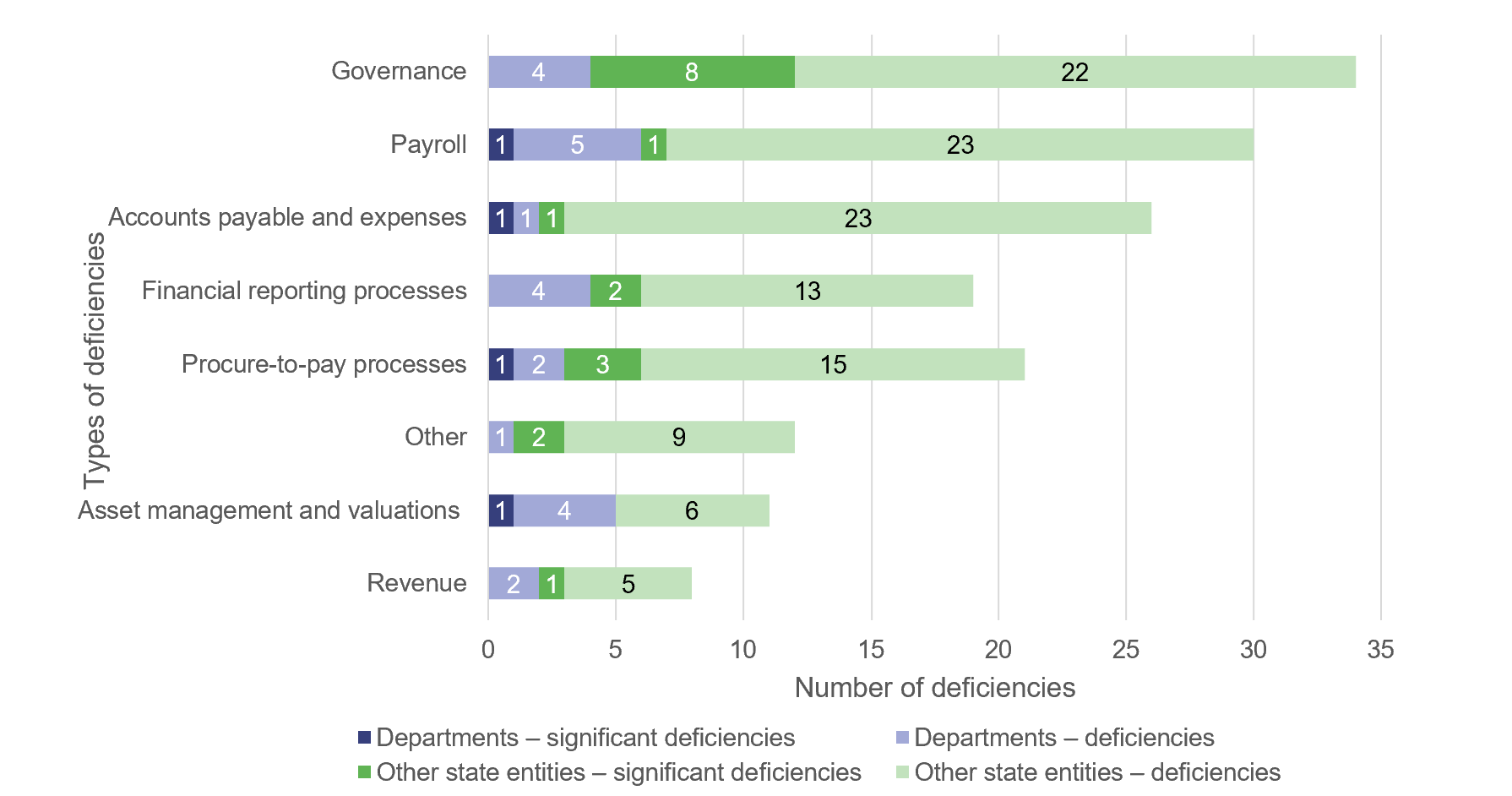

Internal controls are generally effective, but entities still have common weaknesses to address

Overall, we found that the internal controls (excluding those relating to information systems) in place in state sector entities are generally effective but can be further improved.

This year we included all deficiencies at state sector entities in our analysis to provide greater information and areas for attention by entities.

Figure 5A shows the types of deficiencies we have identified across state sector entities in our audits this year.

Note: The ‘Other’ category includes 9 deficiencies mainly related to debtor and inventory management.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Governance

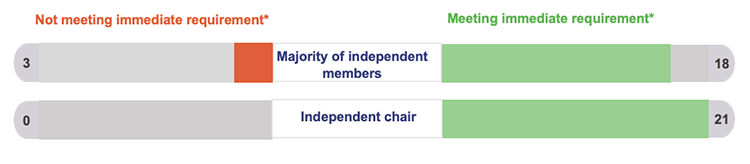

The governance issues included agency compliance with new Queensland Treasury requirements around audit committee membership and policies for special payments.

Audit committees will be independent under changed guidelines

In October 2023, Queensland Treasury released updated Audit Committee Guidelines: Improving Accountability and Performance. These guidelines apply to Queensland Government departments and statutory bodies.

Audit committees play a key role with respect to the integrity of the entity’s financial information, systems of internal controls, and the legal and ethical conduct of management and employees. To be able to perform this role in a way that increases impartiality, objectivity, and public accountability, the committee must be independent.

The new guidelines include a requirement that from 1 July 2025 that all audit committee members are independent. Each member should not be an employee of the entity or another Queensland state government entity.

The new guidelines also include transition arrangements. From October 2023, these required departments and statutory bodies to immediately appoint an independent chair and at least one other independent audit committee member. They also need to have a majority of external committee members from 1 July 2025.

As part of our 2023–24 audits, we analysed whether the departments were complying with the immediate transition arrangements, as shown in Figure 5B.

Note: *These are the immediate requirements from Queensland Treasury’s Audit Committee Guidelines: Improving Accountability and Performance in October 2023.

Queensland Audit Office.

The remaining departments will need to ensure they effectively plan their transition to fully independent membership, so they can meet this requirement from 1 July 2025.

Policies for special payments

Public sector entities can make special payments, including ex-gratia expenditure and other expenditure that is not under a contract. A payment is ex-gratia when it is not due either under a contract or otherwise. In 2023–24, 54 state entities spent $19.6 million on special payments (2022–23: 47 entities spent $19.4 million).

All state sector entities, except for government owned corporations, must include in their annual financial statements the total amount for each type of special payment (for example ex-gratia) and a description of the nature of all special payments greater than $5,000.

We reported significant deficiencies and deficiencies in the controls over special payments, including the need for appropriate policies that define the criteria for making special payments and approval processes. This helps to ensure the appropriateness of payments made. In most cases, transparency of the transaction also supports the integrity of public spending.

In State entities 2023 (Report 11: 2023–24), we recommended that entities implement robust policies and procedures for special payments. Doing so would help those charged with governance and management to ensure the special payments are appropriate, defensible, and transparent.

Those entities that we made specific recommendations to in our audits have largely implemented them. However, we found similar deficiencies across other entities in 2023–24, including:

- insufficient documentation to support special payments

- inconsistent or no framework to determine special payments

- no formal approval of special payments.

The continued use of ex-gratia payments each year can increase the risk of public sector funds being misused, so they should only be made in infrequent circumstances.

Ex-gratia payments are often made using deeds of release, which may contain non-disclosure agreements. While there are situations where non-disclosure agreements might be necessary to protect sensitive information or privacy, it is important to balance the need for confidentiality with the principles of transparency and accountability. Non-disclosure agreements can limit the ability of the public and oversight bodies to scrutinise the reasons and justifications for such payments, and can potentially conceal serious issues that need to be addressed such as misconduct or mismanagement. |

We encourage all entities to take further action on the recommendation we made in State entities 2023 (Report 11: 2023–24):

- all state entities should implement robust policies and procedures that specify when an ex-gratia payment is appropriate and how it should be made

- guidance material should be available and outline who is authorised to approve ex-gratia payments and what constitutes appropriate documentation to support them.

Payroll

Employee expenses remain the largest expense area for the total state sector, increasing by 9.4 per cent in 2023–24 to $36.1 billion. The number of full-time equivalent (FTE) employees across the state sector increased by 15,910 FTE this year (5.8 per cent) to 291,616 FTE employees.

Strong, effective controls ensure the accuracy of payments to employees and reduce the risk of fraud. This year, we found new deficiencies in controls in 6 areas of payroll processing as shown in Figure 5C.

| Areas of payroll deficiencies | Per cent of deficiencies | Importance of addressing deficiencies in a timely basis |

|---|---|---|

| Ineffective review of key pay run processes and controls | 53% | Adequate and timely review of pay run reports mitigates the risks of incorrect payments and enhances overall operational effectiveness. Providing refresher training and procedure manuals with detailed work instructions to staff performing the payroll function helps minimise the risk that employees may be paid incorrectly. |

| Errors in calculations not being detected and employee leave not being recorded | 17% | Robust policies and procedures ensure clarity and consistency in practices for all employees. Effective record keeping for employees’ leave is required to comply with laws and regulations and to ensure accurate processing of employees’ leave entitlements. |

| Lack of completeness or errors in records supporting employee separations | 14% | Consistency in undertaking employee separation processes prevents errors and mistakes, such as incorrect payments. |

| Over and/or underpayments of pay | 10% | Timely reviews of over and underpayments prevents financial loss and reduces reputational risk to the entity. |

| Control deficiencies identified at a payroll service provider | 3% | Risk assessments are required over third-party service providers to minimise operational disruption in the event of a data breach. Appropriate steps should be taken to ensure service providers have a secure IT environment to reduce cyber security risk. |

| Higher duties approved without appropriate delegation | 3% | Approval by an officer with the correct delegation helps ensure accurate and authorised payments are made. Financial delegations establish clear responsibility for financial decisions, promoting transparency and accountability. |

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Entities must have robust payroll controls as illustrated in Figure 5D, so their employees are paid accurately and on time, and to detect errors. These controls also help entities to reduce financial loss, fraud, and legal and reputational risks.

Queensland Audit Office.

Expenses and expense management

Operating expenses for the total state sector increased by 20 per cent in 2023–24 to nearly $33 billion. Expenses include the cost-of-living rebates paid initially to electricity retailers, and higher expenses to support additional health and child safety related services.

Having strong internal controls over expenditure is essential for public sector entities to reduce their exposure to risks such as fraud, overspending, and lack of accountability and transparency.

This year, we found new deficiencies in controls in 6 areas of expenditure processing in accounts payable as shown in Figure 5E.

| Areas of deficiencies in expense management | Per cent of deficiencies | Importance of addressing deficiencies in a timely basis |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate checking of changes to vendor records | 23% | Effective controls over supplier masterfile changes prevents fraud, ensures data accuracy, maintains compliance, streamlines payments, and helps manage risks. |

| Ineffective review of documentation and reports | 19% | Conducting an appropriate review of source documents ensures accuracy, reduces errors and discrepancies, and helps detect and prevent unauthorised or fraudulent transactions, ensuring only legitimate expenditure is recorded. Checking system-produced reports, such as a trial pay report, helps identify and correct errors promptly. |

| Ineffective security over payment files | 16% | Appropriate security of payment files helps to prevent unauthorised transactions, reduce the risk of fraud and loss, and ensure that funds are transferred correctly. Secure payment files protect sensitive financial information from unauthorised access and cyber threats. |

| Non-compliance with financial delegations | 15% | Authorised personnel approving financial transactions reduces the risk of fraud. Financial delegations establish clear responsibility for financial decisions, promoting transparency and accountability. |

| Other – inaccuracies in processing transactions | 15% | Accurate and timely review of documents and reports ensures financial records are reliable and correct. |

| Non-compliance with policies | 12% | Compliance with expense policies maintains financial control, ensures accountability and transparency, and reduces the risk of fraud. |

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

In 2023–24, a Queensland public sector entity was the subject of a substantial vendor fraud attack. Although these threats of fraud are well known, we found 5 entities that still need to improve their controls relating to changes to supplier bank account details.

Enhancing the effectiveness of internal controls over expenses processed by accounts payable as shown in Figure 5F helps to prevent fraud, ensure accurate financial reporting, maintain cash flow, and enhance operational efficiency.

Queensland Audit Office.

Procure-to-pay and contract management processes

We examined procure-to-pay, procurement, and contract management processes and controls, and performed audit testing on contractors and consultants expenses for selected entities across the total state sector.

Elements of policies we considered further included contract management practices, conflicts of interest, and whether value-for-money considerations were assessed early by management. Figure 5G shows opportunities for state entities to improve procure-to-pay and contract management processes.

Procure-to-pay is the end-to-end process of requisitioning, purchasing, receiving, and paying for goods and services within an organisation.

| Focus area | Common opportunities for entities to improve controls, compliance, and transparency in procurement activities |

|---|---|

Policies and compliance Appropriate policies and procedures and compliance with applicable legislation ensure that procurement aligns with the overarching Queensland Procurement Policy 2023. | Clear and comprehensive policies help entities maintain consistent practices and give staff the tools to make informed decisions. |

Documenting approaches to procurement Documenting the rationale for the procurement approach adopted is an important element when demonstrating the appropriateness of a procurement decision. | Documenting the reasons for choosing a specific procurement approach, such as sole sourcing over open tender, ensuring transparency and accountability, and providing a clear rationale for decision-making that can withstand scrutiny and foster public trust. |

Publishing awarded contracts The Queensland Procurement Policy 2023 and Contract Management Framework highlight the importance of publishing awarded contracts. | Publicly disclosing awarded contracts on the Open Data Portal when required enhances accountability and maintains trust in government processes. Key details that need to be disclosed include the contractor, contract value, and scope. |

Whole-of-life costs and contract variations Entities must consider whole-of-life costs associated with the procurement of a contract. This mitigates the risk of excessive use of contract variations without formal reassessment. | Entities should incorporate whole-of-life costs into the procurement process to more accurately reflect total anticipated costs. While variations are common in large projects, they can create significant risks if they are not managed effectively, meaning projects no longer align with the initial scope, budget, and objective. Entities should thoroughly assess and report on contract variations. Where changes fundamentally alter the original contract’s scope or cost, such as adding new services or changing the deliverables, a new contract may be more appropriate to determine if value for money could be achieved by going back to the market. |

Performance and outcomes Closely monitoring performance, and evaluating outcomes after a contract, ensures that public resources are used effectively, contractual obligations are fulfilled, and continuous improvement opportunities are identified for future procurement activities. | Entities should consider enhancing monitoring and reporting by establishing performance metrics for procurement and contract management. Reporting can also assist to drive continuous improvement. |

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

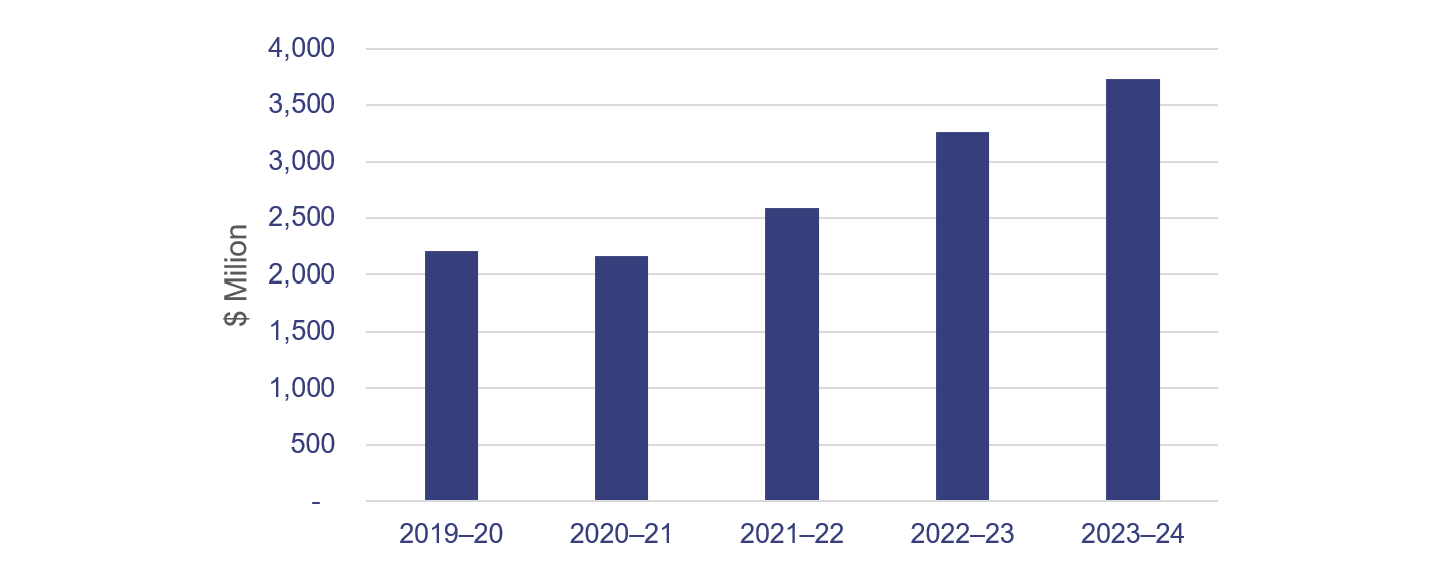

Increase in contractor and consultant spending

Spending across the total state sector on contractors and consultants increased by $474 million in 2023–24 to $3.7 billion, highlighting the importance of achieving value-for-money outcomes. Figure 5H shows contractors and consultants expenses since 2019–20.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from total state sector payments to contractors and consultants reported in audited financial statements.

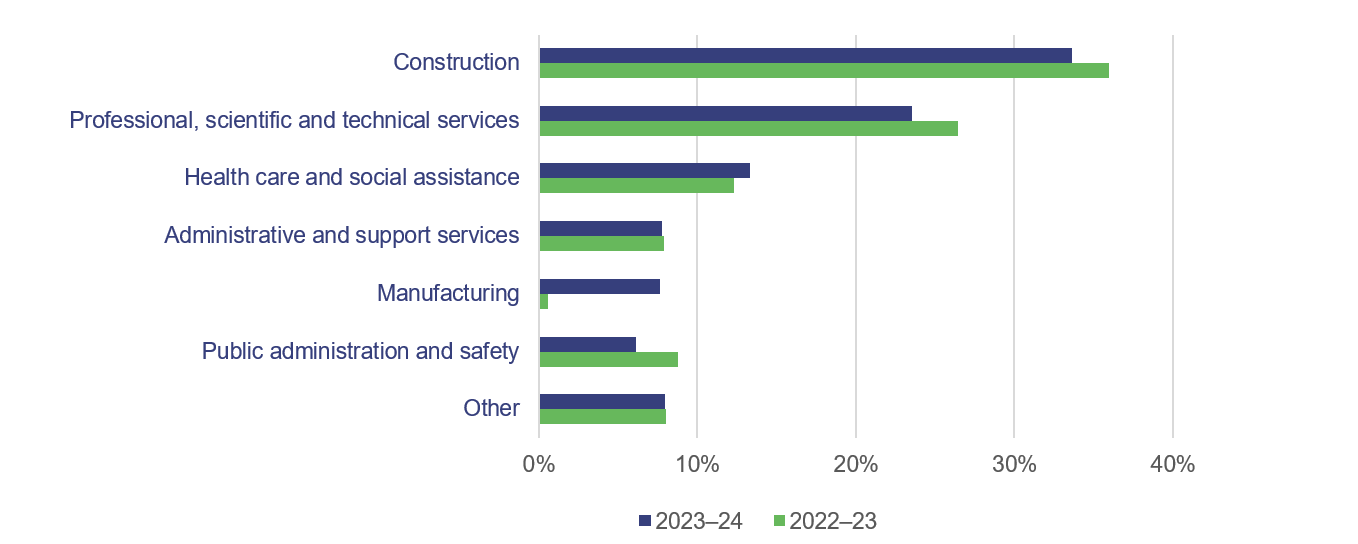

The above diagram only includes contractor and consultant expenditure included in the Statement of Financial Performance (profit and loss). Contractors and consultants expenses related to the construction of assets are also often added to the cost of assets in the Statement of Financial Position (balance sheet). To understand the areas where the state is using contractors and consultants, we analysed departmental expenditure reported in audited financial statements by suppliers for 2022–23 and 2023–24 using the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification framework (ANZSIC). Our review of contractors and consultants expenses is shown in Figure 5I and highlights the largest areas of spending were construction expenses followed by professional, scientific, and technical services.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Presently, there is limited or inconsistent reporting by expenditure type by agency or across government. There may be benefits in performing this analysis to inform procurement and contracting practices, as well as improving strategic workforce planning and identifying skills and capabilities.

Gladstone Ports needs to strengthen its governance and oversight

The Port of Gladstone is Queensland’s largest multi-commodity port (and the fourth largest coal exporting terminal in the world) and is a major economic hub for Central Queensland.

In Transport 2021 (Report 10: 2021–22), we reported on the impact that frequent changes to Gladstone Port’s key management personnel and executives had on its governance structure, reporting, direction, and the board’s ability to enforce the desired decision-making culture. Since this report, we have continued to focus on governance controls. In 2023–24, Gladstone Ports experienced turnover in senior leadership positions.

While management has taken steps to address our previous recommendations, this financial year, we found 4 significant governance deficiencies and a number of deficiencies which related to:

- procurement and recruitment policies and processes not being appropriately followed

- non-compliance with the board charter

- payments being approved outside of authorised delegations

- breach of a conflict management plan

- propriety of decision making by key executives, which can increase the risk of waste of public resources.

Understanding and applying policies are essential to building a positive culture, minimising risks, and creating a consistent and fair work environment, especially when there is a history of deficiencies. It helps reset the tone of the organisation and promote integrity and compliance.

On 13 February 2025, a new Chair of Gladstone Ports was appointed. Management is taking action on our recommendations and is providing regular updates on the progress to the board.